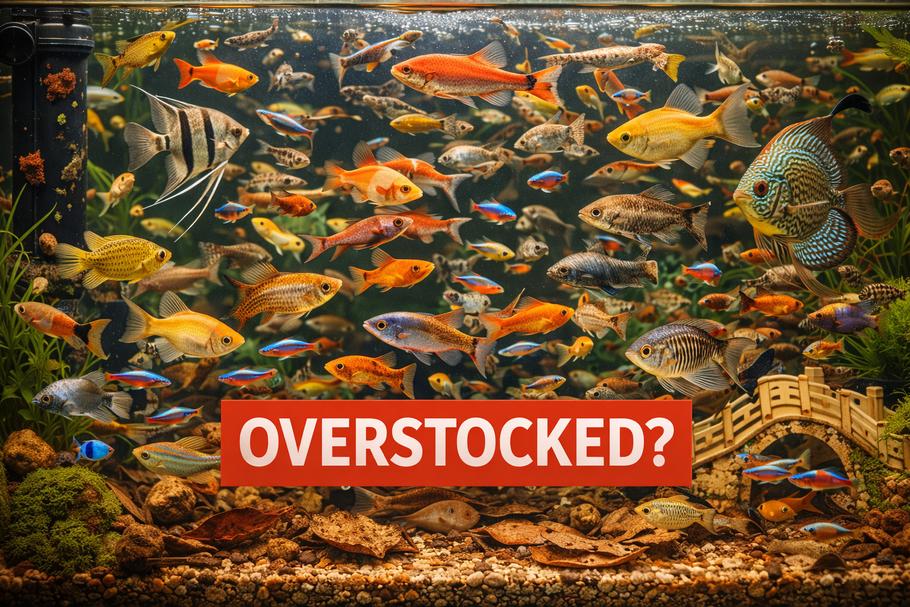

OVERSTOCKING MYTHS VS REALITY

The One Inch Per Gallon Myth: Why Simple Math Fails

Perhaps the most persistent relic of early aquarium literature is the "one inch of fish per gallon" rule. For decades, beginners have been told that a ten-gallon tank can safely house ten inches of fish. While this rule was designed to provide a safe baseline for small, slim-bodied fish like Neon Tetras or Zebra Danios, it fails spectacularly when applied to the modern variety of species available today. The primary flaw in this logic is that it ignores the three-dimensional reality of fish mass and metabolic waste.

Consider the difference between ten one-inch Neon Tetras and a single ten-inch Oscar. While both represent "ten inches" of fish, their impact on the aquarium environment is worlds apart. A ten-inch Oscar has significantly more body mass, consumes vastly more food, and produces an exponential amount of waste compared to a handful of tetras. Furthermore, large-bodied fish require more physical room to turn, swim, and establish territory. When we rely solely on linear measurements, we ignore the biological load—or bioload—that actually dictates the health of the water column.

Another factor the inch-per-gallon rule ignores is the footprint of the tank. A tall, narrow "column" tank and a long, shallow "breeder" tank might both hold twenty gallons of water, but the long tank has significantly more surface area for oxygen exchange. Oxygen enters the water at the surface; therefore, a tank with more surface area can generally support a slightly higher bioload than a deep, narrow one. When planning your stock, look at the swimming habits of your chosen species. Fish like larger tetras for the community tank need horizontal swimming space, whereas bottom-dwellers like Corydoras care more about floor space than total water volume.

Bioload vs. Visual Space: The Hidden Chemistry

When hobbyists talk about overstocking, they are usually referring to one of two things: physical crowding or biological overload. Physical crowding is easy to see; the fish look cramped, they bump into each other, and there is no "negative space" in the water. Biological overload, however, is invisible and far more dangerous. It refers to the point where the beneficial bacteria in your filter can no longer process the ammonia and nitrites produced by the inhabitants' waste at a rate fast enough to keep the water non-toxic.

Every fish added to the system increases the demand on the nitrogen cycle. In an overstocked tank, even a minor hiccup—like a missed water change or a slight overfeeding—can trigger a massive ammonia spike. This is why "heavy feeders" like Goldfish or Plecos are often the catalysts for aquarium crashes. Even if the tank looks empty, these high-waste species can push a filter to its limit. If you are struggling with persistent algae or cloudy water, you might be dealing with an invisible overstocking issue. In such cases, choosing the right algae-eater can help, but it won't fix a fundamental imbalance in your bioload.

To manage bioload effectively, you must understand the "carrying capacity" of your specific setup. This is influenced by:

- Filtration capacity: Is your filter rated for a tank larger than the one you own?

- Plant density: Live plants act as a secondary filter by absorbing nitrates.

- Water change frequency: More fish require more frequent and larger water changes to dilute waste.

- Substrate depth: Deep gravel beds can trap detritus, contributing to the waste load.

Species Compatibility: Why Behavior Trumps Math

Even if your filtration is powerful enough to keep the water crystal clear, your tank can still be "overstocked" from a behavioral standpoint. This is where many intermediate hobbyists run into trouble. They master the chemistry but ignore the social dynamics of the species they keep. Overstocking often leads to heightened aggression, as fish are forced to compete for limited territory, hiding spots, and food.

For example, many Cichlids are notoriously territorial. In a sparsely decorated tank, a dominant male may claim the entire bottom half of the aquarium, effectively "overstocking" the tank by making it impossible for other fish to exist safely. Conversely, some keepers use a technique called "controlled overstocking" for African Cichlids to spread out aggression, but this requires extreme filtration and experience. For the average hobbyist, it is better to provide ample room. If you are interested in these complex social dynamics, researching what are the best cichlids for a community tank is a vital first step in ensuring a peaceful environment.

Compatibility also extends to activity levels. A group of active, boisterous Giant Danios might physically stress out a slow-moving, long-finned Angelfish simply by darting around the tank constantly. Even if there is no direct nipping, the "visual overstocking" of high-energy fish can lead to chronic stress for shyer species. Chronic stress suppresses the immune system, making your fish far more susceptible to identifying and treating the most common cichlid diseases like Ich or Velvet. A tank that is quiet and balanced is always healthier than one that is bustling but stressed.

Signs Your Aquarium is Reaching Its Breaking Point

How do you know if you have crossed the line? Often, the signs of overstocking are subtle before they become catastrophic. One of the first indicators is the "nitrate creep." If your nitrate levels are consistently above 40 ppm even with weekly water changes, your bioload is likely too high for your current maintenance routine. High nitrates over time can lead to stunted growth, poor coloration, and "old tank syndrome," where the water chemistry becomes so unstable that adding any new fish results in immediate death.

Watch your fish for behavioral changes. If you notice fish gasping at the surface in the morning, it may be a sign of low dissolved oxygen—a common side effect of having too many respirating organisms (both fish and bacteria) in a confined space. Other red flags include:

- Frayed fins: A sign of nipping or bacterial rot due to poor water quality.

- Shy fish staying hidden: Indicators that the open water is too chaotic or aggressive.

- Recurring fungal infections: Evidence of a stressed immune system.

- Unexplained deaths: Often the final warning that the ecosystem has collapsed.

It is important to remember that fish grow. A "cute" two-inch Silver Dollar at the pet store will eventually become a dinner-plate-sized powerhouse. Beginners often stock their tanks based on the size of the fish today, rather than their potential size in two years. Always research the adult size and social requirements of a species before bringing it home. If a fish requires a school of six to feel safe, but you only have room for two, you shouldn't buy them; a small group of stressed schooling fish is more of a burden on the system than a properly sized group in an appropriately sized tank.

The Ethics and Science of High-Density Habitats

There is a segment of the hobby that purposefully overstocks tanks, usually in high-tech planted setups or dedicated predator tanks. While possible, this "overclocking" of an aquarium requires a high level of technical skill and a significant time commitment. These systems often utilize sump filters, UV sterilizers, and automatic water changers to maintain stability. For most home aquarists, however, the "reality" is that less is more. A lightly stocked tank is much more forgiving of mistakes and far more rewarding to watch, as the fish exhibit more natural, relaxed behaviors.

When you provide ample space, you get to see the full repertoire of a fish's personality. You see the intricate mating dances of Gouramis, the playful schooling of Rummy Nose Tetras, and the meticulous scavenging of Corydoras. In an overstocked tank, these behaviors are often replaced by a "survival mode" where fish are constantly on edge. Ethically, as keepers, our goal should be to provide an environment that mimics the natural density of their wild habitats, which are almost always vastly more spacious than any glass box we can provide.

Practical tips for maintaining a healthy balance include:

- Under-stock and over-filter: Buy a filter rated for twice your tank size.

- Add fish slowly: Give your bio-filter weeks to adjust between additions.

- Prioritize "cleaner" species: Choose fish with lower metabolic rates.

- Use live plants: They provide oxygen, cover, and waste processing.

- Test water weekly: Don't guess; use a liquid test kit to know your levels.

Takeaway: Finding the Perfect Balance for Your Tank

The "reality" of overstocking is that there is no single number that works for every aquarium. It is a sliding scale based on your equipment, your choice of species, and your dedication to maintenance. While myths like the inch-per-gallon rule offer a tempting shortcut, they ultimately do a disservice to the living creatures in our care. By focusing on bioload, behavioral compatibility, and environmental stability, you can create a display that is not only beautiful to look at but also a healthy home for its inhabitants for years to come.

If you find yourself constantly battling water quality issues or aggressive fish, it might be time to re-evaluate your stocking list. Sometimes, the best thing you can do for your aquarium is to remove a few fish and give the remaining residents the room they need to shine. For more in-depth guides on creating the perfect habitat, continue exploring our database of species-specific care guides and equipment reviews. Your fish will thank you for the extra breathing room!

MOST RECENT ARTICLES